Up until yesterday, I wrote all of my blog posts in Mint Flavoured Markdown and rendered them into HTML with a Python script I wrote called build.py. Build.py was very helpful in simplifying the process of writing new blog posts. The final version of build.py is archived here.

I spent nearly a month developing build.py, so the speed at which I completely abandoned it in favour of Hugo is noteworthy.

Reasoning

Many of my projects were developed in an effort to solve a current problem or avoid a future problem. This switch to Hugo is not one of them. Build.py worked perfectly fine, I just felt like Hugo was much better than what I currently had.

Performance

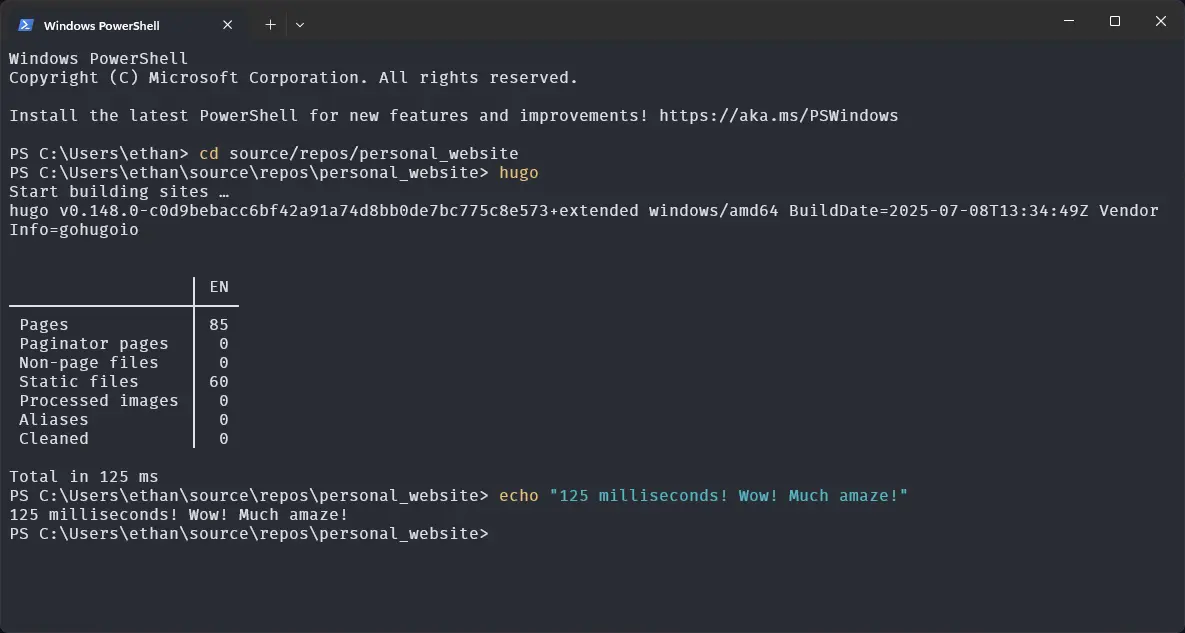

Hugo is blazingly fast. As of today (July 10), a full Hugo build of my site takes 125 milliseconds.

To put that in perspective, let’s imagine that I connected my laptop to a train horn and rigged Hugo such that the instant the site build started, it would trigger the train horn. Now let’s imagine that you’re standing only 42.9 meters (one and a half basketball courts) away. Hugo would finish its build before the sound from the train horn reached you. And that’s only counting the time for the sound wave to reach your location! In the time it would take for you to actually process the sound and react to it, Hugo could have built the site two and a half additional times.

And this is only for a full build. If I only re-build a single page, it takes as little as 9 milliseconds (I’ve seen it at 3ms a few times, but it averages closer to 7-10). To expand on the train horn analogy, if my laptop-train-horn apparatus was at the foot of a king-sized bed while you were at the other end, the Hugo build would complete before you went deaf from the train horn 3 meters away from your ears.

Hugo builds are, for all practical purposes, instantaneous. This means I can view changes in real time on my browser, because Hugo rebuilds the page two orders of magnitude faster than the browser can refresh. In fact, Hugo has this functionality built-in with the “hugo server” command.

In contrast, build.py took 2-3 seconds to build, and didn’t have this functionality to only rebuild specific pages. You’d have to be standing at the tip of three Eiffel Towers balanced on top of each other in order for build.py to finish before the sound from the train horn reached you.

Hugo and build.py aren’t even in the same league in terms of build speed. This is due to Hugo being built in Go rather than Python. The specifics of why using a different language makes such a difference are beyond the scope of this post, but here’s a neat article that explains it without too much jargon.

Built-in Functionality

Hugo has a lot of features, and all of them are built-in, meaning I didn’t have to code them. For example, Hugo natively handles tags, which it calls taxonomies for some reason. Build.py had tags too, but they were a lot of work to implement and added a lot of complexity. Hugo’s taxonomies were still a lot of work for its developers to implement (much more than my crude tags system), but critically I didn’t have to do any of that work, so it isn’t relevant.

Modularity

Hugo strongly encourages DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) code. For example, each page’s head section (that defines things like the favicon and and page title) is defined exactly once in the entire codebase: in layouts/_default/baseof.html. Every single layout (including blog posts like this one, taxonomy pages, etc.) is rendered from the same basic template.

I could have implemented something like this in build.py (at the expense of performance and complexity), but I didn’t, so each template had to redefine things like the head section. This approach gave me slightly more flexibility, but came at the cost of adding a bunch of repetitive definitions I had to manually synchronize across templates.

Shortcodes

Hugo also includes shortcodes, which are inline templates, very similar to the Web Components that I was using before. The big difference is that shortcodes render at build time, whereas Web Components render on page load. This means that your computer had to render the Web Components, which introduced performance overhead and meant that if you just refused to render it (by turning JavaScript off), my site didn’t work. Hugo shortcodes give me the same templating functionality without sacrificing performance or compatibility.

Maturity

As much as making your own versions of existing tools is smiled upon for personal projects, it’s also frowned upon in a professional setting. It’s impractical and selfish to waste developer time on making a worse version of something that already exists, so learning how to use the industry standard frameworks is highly important to being a useful developer. Hugo is a mature, widely-used SSG, whereas build.py is not.

Tradeoffs

There are a few consequences of switching to Hugo, though.

Reduces Charm

There’s a certain air to being able to say “I made this without any prebuilt libraries” on my personal website’s project page gives. I’m going to call it “charm”, but it’s probably closer to “smugness”. Anyways, using a prebuilt SSG like Hugo means that I can’t honestly claim that this site is built using only my own tools. I think that this significantly reduces the overall charm and impressiveness of the site.

There are a few asterisks to this…

- I still made literally every asset except for the SSG myself

- I proved that I was capable of making a comparable SSG in the form of build.py

- I switched to Hugo because I thought it was better, not because I wasn’t able to continue developing build.py

…but there’s no getting around that the SSG is a very important part of any static site, and the one I’m using wasn’t made by me.

Less Flexible

Hugo has a fairly rigid project structure. Each type of content (e.g. blog post) is allowed to have a single template (individual blog post) and a list template (all blog posts). Same goes for tags: I can have a taxonomy template (individual tag) and a term template (all tags).

There are ways to add custom layouts, but implementing custom layouts is far more complicated than just using the ones in Hugo’s default structure. Once you venture outside of the Hugo-idiomatic architecture, you start having to fight Hugo to produce the desired output.

Hugo’s default structure happened to line up almost exactly with that of build.py, but now I’m more or less locked into this structure. With build.py, it would be about the same amount of work to implement a new layout type as it was to implement tags. With Hugo, it’s far more complicated.

Unfamiliar Language

To process and render templates, build.py used a combination of Python and Jinja, both of which are languages which I’m familiar with. Hugo, on the other hand, uses the Go templating language for layouts and shortcodes, which I didn’t even know existed until I started using Hugo. It’s similar in concept to Jinja, but uses different syntax and has a few other differences.

For example, here’s the original Python implementation of the MFM media tag from build.py.

def embed_media_tag(match):

img_tag = match.group(1)

src = match.group(2).strip()

alt_match = re.search(r'alt=["\']([^"\']*)["\']', img_tag)

original_alt_text = alt_match.group(1) if alt_match else ""

contains_gif = "GIF" in original_alt_text

contains_nofig = "NOFIG" in original_alt_text

processed_alt_text = original_alt_text.replace("GIF", "").replace("NOFIG", "").strip()

if contains_gif or contains_nofig:

if alt_match:

img_tag = re.sub(

r'(alt=["\'])([^"\']*?)(["\'])',

rf'\g<1>{processed_alt_text}\g<3>',

img_tag,

count=1

)

youtube_match = re.match(r"https?://(?:www\.)?(?:youtube\.com/watch\?v=|youtu\.be/)([\w-]+)", src)

if youtube_match:

video_id = youtube_match.group(1)

return f"""<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/{video_id}"

frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>"""

video_exts = (".mp4", ".webm", ".ogg", ".mov")

if src.lower().endswith(video_exts):

alt_attribute_str = f' alt="{processed_alt_text}"' if processed_alt_text else ""

video_class = "gif" if contains_gif else "video"

controls_attr = "autoplay loop muted playsinline" if contains_gif else "controls"

return f"""<figure><video class="{video_class}" src="{src}"

{controls_attr}{alt_attribute_str}></video></figure>"""

if contains_nofig:

return img_tag

return f"<figure>{img_tag}</figure>"

And here’s the Hugo shortcode I wrote as a Go template to replicate some of that functionality.

{{ $src := .Get "src" }}

{{ $alt := .Get "alt" }}

{{ $is_gif := findRE "GIF" $alt }}

{{ $is_nofig := findRE "NOFIG" $alt }}

{{ $alt_processed := replace (replace $alt "GIF" "") "NOFIG" "" | strings.TrimSpace }}

{{ if $is_nofig }}

<img src="{{ $src }}" alt="{{ $alt_processed }}" />

{{ else }}

<figure>

{{ if strings.HasSuffix $src ".webm" }}

{{ if $is_gif }}

<video class="gif" src="{{ $src }}" autoplay loop muted playsinline alt="{{ $alt_processed }}"></video>

{{ else }}

<video class="video" src="{{ $src }}" controls alt="{{ $alt_processed }}"></video>

{{ end }}

{{ else }}

<img src="{{ $src }}" alt="{{ $alt_processed }}" />

{{ end }}

</figure>

{{ end }}

The Go template is significantly more concise, but it’s also simplified compared to the Python script, and it doesn’t replicate all of the functionality (because there were already prebuilt shortcodes for iFrames and YouTube embeds so I didn’t bother adding them to the figure shortcode). Also, I don’t understand this code in the same way that I understand the Python code. Go templating is a new language for me, and the syntax still feels alien.

Conclusion

I didn’t make the decision to switch to Hugo lightly, but I’m pretty content with my choice overall. Porting my site to Hugo was a valuable learning experience, and I’m excited to add Go templates to my toolbox. I’m delighted at how Hugo instantly builds my site and refreshes my browser the moment I make a change to the Markdown. And I was spared from having to come up with a new name for build.py because that generic name wasn’t going to fly for much longer.

~Ethan